Climbing Mount Rainier

Climbing Mount Rainier: At 14,411 feet, Mount Rainier—or Tahoma, as regional American Indian tribes called it—falls a little short of the loftiest Sierra Nevada and Southern Rocky Mountain peaks. You can make a mighty strong argument, however, that Rainier’s the single most impressive summit in the conterminous United States: an all-around monster of a mountain, more topographically prominent than any Lower 48 contender and crowned with an icecap hundreds of feet thick.

Mount Rainier’s more than just awe-inspiring to behold (as millions do on clear days from the cities of the Puget Sound basin). It’s also a world-famous mountaineering destination, coveted by climbers in its own right and—given its great bulk and sometimes ferocious maritime weather—as a challenging training ground for loftier peaks such as Denali or the Himalayan giants.

A Fiery Snowpeak

Like the other iconic snowpeaks of the Cascade Range, Mount Rainier is a stratovolcano (also called a composite volcano): one built by layer after layer of lava and pyroclastic flows (avalanches of hot volcanic rock and gases). The Cascades, part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, owe their volcanic energies to the subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate beneath the North American Plate. This ongoing tectonic process ensures at least some of the High Cascade volcanoes, Rainier among them, may erupt in the future as they’ve done numerous times over the past several hundred thousand years.

Mount Rainier’s huge, lumpy crown includes three peaks: 14,112-foot Liberty Cap on the north, 14,158-foot Point Success on the south, and the apex, Columbia Crest, which tops the summit’s Crater Rim. The irregularity of its profile attests to a volatile history of lava swellings, violent eruptions and landslides, and the erosion of glaciers (which we’ll get to below). The most dramatic event in Rainier’s “recent” (by geological standards) past surely was the Osceola Mudflow, a titanic lahar of some 5,600 years ago created by the collapse of Rainier’s former summit, which rose perhaps to some 15,000 feet. The Osceola Mudflow roared down Rainier’s northeastern slopes and into the valley of the White River, ultimately mantling part of the Puget Trough lowlands.

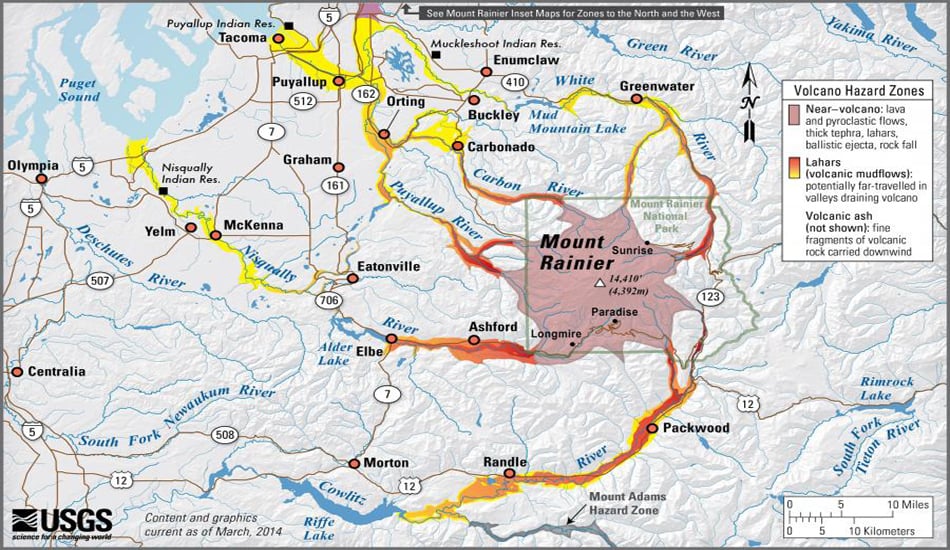

Simplified hazards map showing the potential impact areas for ground-based hazards during a volcanic event. Image Courtesy of the US Geological Society

(Back when that happened, of course, the basin of Puget Sound was far less populated than it is today. Geologists consider Mount Rainier to be North America’s most dangerous volcanoes—and one of the most dangerous on the planet—especially because of the potential for future lahars like the Osceola and how many Washingtonians would be impacted by such an event. Rainier hasn’t formally erupted since the 19th century, although the volcano has kept folks on notice with occasional steam emissions—not to mention plenty of avalanches and rockfalls.)

Due to its enormous mass, impressive elevation, and proximity to the storm factory of the North Pacific, Rainier lays claim to more ice than the rest of the Cascade Range combined: some 35 square miles of it, in fact. That icecap includes 26 main glaciers, among them that with the largest surface area in the Lower 48—the Emmons at 4.3 square miles—and that reaching the lowest elevation: the Carbon, which snouts out at 3,600 feet and which, furthermore, is Rainier’s most voluminous glacier.

Today’s glaciers, though, are nothing compared to the ones that snaked down from the volcano during the height of the Pleistocene ice ages, which penetrated the Puget Trough lowlands some 35 miles from the mountaintop.

As we’ve already alluded to, the look of Rainier reflects an ongoing battle between glaciation and volcanism. The peak gains bulk from magma swellings and lava eruptions, while glaciers fluctuating in size over time do their best to gnaw that rock edifice away. The mightiest headwall in the Cascades lies on Rainier’s north face (where glaciers have been biggest and most active): the Willis Wall, marking Carbon Glacier’s amphitheater. This 4,000-foot cliff both inspires climbers and gives them the willies, given the avalanches and rockfall that frequently sweep down it; this is among the most hazardous climbs on Rainier.

Speaking of climbs, let’s get on with the mountaineering! Here we’ll consider the two most popular approaches to Mount Rainier’s summit—the Disappointment Cleaver and Ingraham Glacier routes out of Camp Muir—and also give some shout-outs to a handful of alternatives.

Summiting From Camp Muir: The Disappointment Cleaver & Ingraham Glacier Routes

Climbing Mount Rainier along these routes, crowded as they are, makes a fantastic choice for those seeking more experience with snowpeak mountaineering as well as parties with limited time. Two of the best Rainier guiding companies, RMI and Alpine Ascents, both lead Camp Muir summit climbs that actually double as instructional courses in glacier travel. You will also need to make sure you have proper mountaineering equipment.

Camp Muir lies at about 10,000 feet on Rainier’s southeastern flanks. It gets its name from the great Scottish-American adventurer, botanist, and preservationist John Muir, who camped at this spot—then called Cloud Camp—in 1880 on a successful climb of Tahoma (the sixth one on record) via today’s Gibraltar Ledges Route. (Conditions were on the inclement side: Muir wrote, “The night was like a night in Minnesota in December.”) Among Muir’s climbing party was Philemon Beecher Van Trump, who’d made the inaugural recorded ascent of Mount Rainier 10 years earlier with Hazard Stevens. As Mike Gauthier points out in Mount Rainer: A Climbing Guide, Muir and Van Trump both later lobbied, as members of the Sierra Club, for Mount Rainier to become a national park (which did indeed happen in 1899).

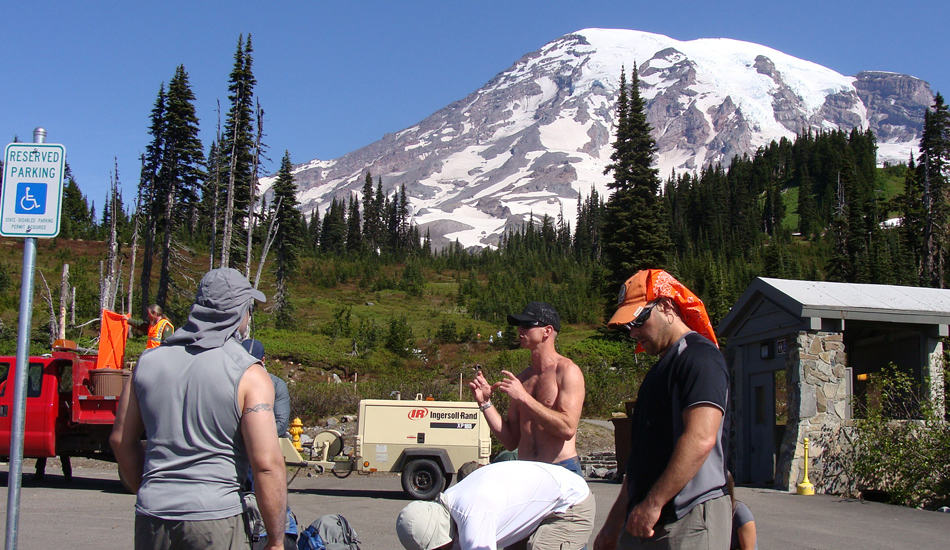

Your first day of climbing Mount Rainier involves reaching Camp Muir from Rainier’s most popular destination, Paradise, an ascent of some 4,500 feet and four or five hours. The route—also popular among hikers—tracks up Pebble Creek and then up the Muir Snowfield to Camp Muir. This may be a super well-trammeled approach, but that doesn’t mean it’s without hazards: During whiteouts, hikers and climbers alike have trudged off course into crevasses of the Muir Snowfield’s edging glaciers or too dangerous cliffs east of McClure Rock, Anvil Rock, and Camp Muir.

Muir Snow Field Approaching Camp Muir

The Paradise-to-Camp Muir trek serves up plenty of gobsmacking views, including of the great Nisqually Glacier to the west and—if it’s clear—fine prospects of the Tatoosh Range to the south and, farther out along the Cascade Highlands, Mount St. Helens, Mount Hood, and Mount Adams.

Mt Adams to the left and Mt. Hood to the right

With its huts, outhouses, and ranger outpost, Camp Muir’s a major hub, and depending on your guide and your itinerary, you may spend the night here in an established hut or in a tent. On RMI’s five-day climb along this route, you’ll actually spend a full day acclimatizing and practicing skills at Camp Muir and sleep the second night here before making the summit push.

From Camp Muir, the classic approaches to Rainier’s summit proceed via the overlapping Disappointment Cleaver or the Ingraham Glacier Direct routes. On an RMI or Alpine Ascents climb, your guides will make the call as to which you’ll follow. In general, the Ingraham Glacier Direct’s a more popular winter climb, while the Disappointment Cleaver alternative draws most climbers in the summer.

From Camp Muir, you’ll cross the Cowlitz Glacier and then slip over to the Ingraham Glacier via a pass (Cathedral Gap) in the Cathedral Rocks Ridge separating the two ice tongues. (The Cowlitz and Ingraham glaciers merge below the Cathedral Rocks.) Ingraham Flats on the far side of Cathedral Gap marks an alternative campsite to Camp Muir; the three-day Muir Climb offered by Alpine Ascents uses Ingraham Flats as the camp on the second night to provide an early shot at the summit on the final day.

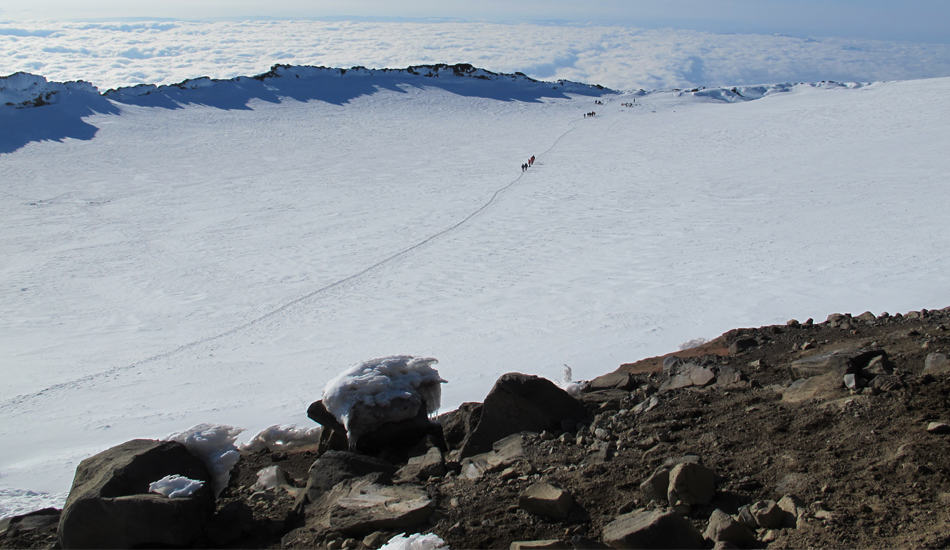

Ingraham Flats From Disappointment Clever

It’s on the Ingraham Glacier that the two standard routes diverge. You’ll either cut across to Disappointment Cleaver, a rock ridge separating the Ingraham from the Emmons Glacier, or proceed up the Ingraham via its headwall (the Ingraham Glacier Direct route). From Disappointment Cleaver, you’ll marvel at the craggy fin of Little Tahoma, an andesitic relic of Rainier’s former eastern shoulders that help create its iconic profile as viewed from the south or north. The Ingraham Glacier Direct route, meanwhile, shows off some awe-inspiring crevasses and seracs.

Both routes attain the Crater Rim, from which Rainier’s summit—Columbia Crest—awaits less than an hour’s climb away.

A Few Other Rainier Routes

There are a number of other summit approaches out of Camp Muir, including the Gibraltar Ledges, the route followed during the first documented ascent of Mount Rainier by Van Trump and Stevens in 1870. (Gibraltar Rock is a lava rampart below Columbia Crest that makes another of the mountain’s most distinctive landmarks.) Camp Schurman on the northeast side of the mountain provides another very popular jumping-off point for summit attempts via the Emmons and Winthrop glaciers.

Another good south-side approach when climbing Mount Rainier, commencing from Paradise is the Kautz Glacier Chute, more demanding (and less busy) than the Disappointment Cleaver/Ingraham Glacier Direct options on account of its steeper gradient. The Kautz Glacier gets its name from Lieutenant August Valentine Kautz, whose party almost got to the summit way back in 1857 along this course.

The “Chute” in question is the narrow and precipitous upper trunk of the Kautz Glacier, shouldered by the Kautz Cleaver to the west (another climbing route) and the Wapowety Cleaver and Kautz Ice Cliffs to the east. A highlight of the route is eyeballing those intimidating Ice Cliffs from the aptly named Camp Hazard, at 11,300 feet the highest-elevation designated mountaineering camp on Rainier and one in which Mike Gauthier (again in his Mount Rainier: A Climbing Guide) advises you do not bed down given the risk of ice and rock careening down from the frozen scarp just above.

Some other exciting Rainier route includes the Edmunds Glacier up to the Mowich Face under Liberty Cap on the northwest side and the arduous Liberty Ridge climb alongside the Willis Wall.

Success on the Mountain

Every route climbing Mount Rainier offers its own challenge and scenery, and climbing in different seasons further multiplies the variety of experiences on these hallowed mountainsides. In short, you can pursue a lifetime’s worth of adventure up on this epic stratovolcano.

You need a climbing pass (and, if you’re going to overnight on the mountain, a wilderness permit) from the National Park Service; check out this page to familiarize yourself with all the regulations.

Even if you hope to someday do an independent climb up Rainier, we recommend making at least your first few attempts with the help of guides such as RMI or Alpine Ascents. Tahoma’s full of hazards, from plunging crevasses and slide-prone headwalls and ice cliffs to the omnipresent threat of storms, which may sock the summit in for days on end. As on any snowpeak, you need to exercise lots of common sense up here, and you should never attempt the summit if conditions look too risky—even if you’re only a few hundred feet away. If Rainier seems a little too daunting for your first climb you may consider Mount Baker as it is very similar just not as big.

Want some informative background reading on Mount Rainier routes? We recommend the aforementioned Mount Rainier: A Climbing Guide by Gauthier as well as Fred Beckey’s classic Cascade Alpine Guide: Vol. I.

Find the Equipment you will need for Climbing Mount Rainier

View Recent Posts

Fall Hiking Gear

The Best in 2020 Fall Hiking Gear Looking for information on fall hiking gear? No offense to the other seasons, but Autumn is the best time to hike throughout much of the Northern [...]

Sayulita Vacation

Crimson Skies of Sayulita If you are looking for an off-the-beaten-path travel destination, a great place to surf, reflect, rejuvenate, and soak up the sun then look no further than a Sayulita Vacation. This [...]

Big Island Hawaii Things To Do

Big Island Hawaii Things To Do, A Journey of Beauty and Contrast The big island Hawaii has a history datable to 1,500 years ago when a small fleet of canoes landed on the island's [...]

Climbing Mount Rainier

Climbing Mount Rainier Climbing Mount Rainier: At 14,411 feet, Mount Rainier—or Tahoma, as regional American Indian tribes called it—falls a little short of the loftiest Sierra Nevada and Southern Rocky Mountain peaks. You can [...]

Iceland Adventure Travel

Iceland — The land of Fire and Ice Iceland Adventure Travel; Iceland is home to just under 325,000 people who live in a habitable area of 103,000 square kilometers. The largest city is the [...]

Dominican Republic Treehouse Adventure

The Dominican Republic Treehouse Adventure in the Caribbean PRICE FOR 2 PEOPLE $597.00 (Regularly [...]

Climbing Mt Baker

Climbing Mt Baker for the First Time Climbing Mt Baker: Amazing adventure lies just outside your door and such is the case for residents of the Pacific Northwest. A string [...]

Experiencing Joshua Tree National Park

Experiencing Joshua Tree National Park A few years ago while on vacation in Palm Desert, we made the decision to go for a drive and explore the surrounding area outside [...]

Hiking Trail Shoes

Hiking & Trail Shoes - Earth Gear Review Altra Trail Shoes Prior to our trip to Sedona we were approached by Altra Running and offered shoes to test on the desert trails [...]

Sedona Arizona

The Magic of Sedona Arizona We recently traveled to Sedona Arizona to experience first-hand the magical splendor of this beautiful community. We booked our flight and accommodations through TripAdvisor and were extremely pleased with our choice [...]

Sedona Hiking West Fork Trail

Sedona Hiking - West Fork Trail Situated in Oak Creek Canyon 10.5 miles north of Sedona along SR 89A, The West Fork Trail is one of the most beautiful Sedona hiking trails. [...]

Sedona AZ Courthouse Butte Loop

Sedona AZ Hiking - Courthouse Butte Loop Near the Village of Oak Creek, the Courthouse Butte Loop is a pleasant 4.2 mile trail circling Bell Rock and Courthouse Butte. It is best to [...]

Hiking Sedona Brins Mesa Outlook Trail

Hiking Sedona - Brins Mesa Overlook Trail If your looking to get out and turn your hike into a leg burning exercise, then you have to take the Brins Mesa Overlook Trail. The [...]

Wildlife Safety Hiking

Wildlife Safety While On The Trail Bears aren’t the only large animals hikers in North America need to be cognizant of for their own safety. Here are some tips on pursuing good neighborly relations [...]

Bushwacking

Bushwacking Your Way Through the Wilderness Bushwhacking reaps many rewards. Cross-country ramblers often stumble upon stirring sights few human eyes have laid eyes upon: hidden waterfalls, secret wildflower glades, unknown old-growth groves, remote vantages [...]

Cabo San Lucas

Explore Cabo San Lucas Mexico Cabo San Lucas on the southern tip of Baja California is one of the most lauded beach getaways in the Western Hemisphere. Famed for its nonstop nightlife, its heaven-minted [...]

Bora Bora Adventure

The Magic of Bora Bora Bora Bora (or Porapora, in the traditional Polynesian spelling) must be one of the most celebrated islands in the world: a place that embodies many people’s ideal of a [...]

Amalfi Coast Italy

Positano Amalfi Coast Campania Italy Not many seashores claim the kind of prestige enjoyed by Italy’s Amalfi Coast, the Sorrentine Peninsula’s southern riviera along the Tyrrhenian Sea. Dreamlike towns—Positano, Amalfi, Ravella—drape themselves over sharply plunging [...]

Camping Glacier National Park

Camping Glacier National Park Information Camping Glacier National Park; Glacier National Park, together with the adjacent (and smaller) Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta, encompasses some of the most gorgeous mountain scenery in North America. [...]

Camping Yellowstone

Camping Yellowstone National Park Camping Yellowstone National Park; Yellowstone may well be the most famous national park in the world; in any case, it can proudly lay claim on being the oldest, established back [...]

Leave A Comment